Sven Mildner

In his draft for the Reinterpretation of Claudius Ptolemy’s Germania Magna – using computer-aided distortion analysis of a medieval map representation by Donnus Nicolaus Germanus – and considerations of post-glacial geodynamics of Europe, the author describes his assumption that Germania Magna underwent a far more extensive landscape transformation in geologically recent times than previously assumed. This transformation may have been caused by post-glacial land uplift in the Holocene or potentially by a reactivation of the Caledonian Deformation Front (CDF) during a late activity phase of the Alpine orogeny, accompanied by tectonic activities in the upper Earth’s crust. Additionally, the possibility that a cosmic impact event triggered such a reactivation of the CDF is not excluded.

The conditions expected to justify the described process likely align with hitherto misattributed or incorrectly dated large-scale fracturing events, which might have led to significant earthquakes in Central Europe over several centuries. These seismic events may even have been documented in medieval historical records.[1]

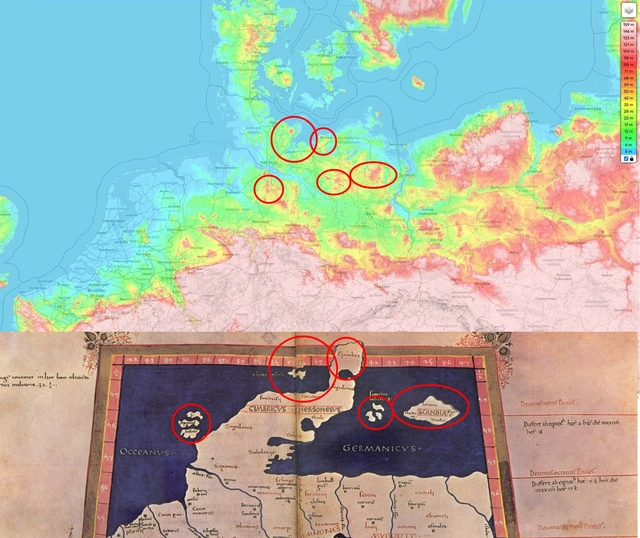

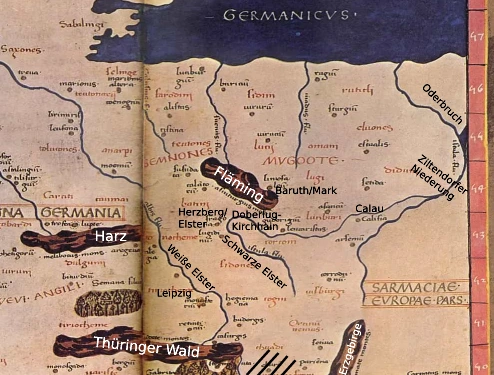

The territory of historical Germania Magna, as described by Ptolemy, corresponds in this interpretation broadly with the territory of present-day Germany but excludes areas of modern Poland, as some earlier interpretations have suggested. During the Holocene, probably still in the early Iron Age (Hallstatt), significant parts of the Central European Basin may have been submerged under a shallow shelf sea. On Ptolemy’s map, the Jutland Peninsula (modern Denmark) appears either disconnected from the mainland or not yet formed as a discernible landmass. The coastline is shown approximately 150 kilometers further south than today, just slightly north of modern-day Berlin. This conclusion is based on the geometric ratios and distance proportions derived from the map, utilizing significant reference points. Notable landmarks include the Fläming region, particularly the town of Baruth/Mark in the northeastern part of the elevation, as well as the Oderbruch and the Ziltendorf Lowland at the map’s eastern edge. The southern and western borders of Germania Magna are marked by the Danube (Danubii or Danubius flu.) in the south and the Rhine (Renus fluvius) in the west and serve as further reference points for this interpretation.

Furthermore, Ptolemy defines the eastern border of Germania Magna by the Sarmatian Mountains (Sarmate Montes) and a river called Vistula Fluvius (Vistula flu.). Considering that the Central European Basin, as previously mentioned, was assumed to have been covered by a shallow sea, it follows that the coastline was located significantly further south. Consequently, the river’s mouth would also have been situated much farther inland than assumed in earlier interpretations. This shift offers a revised reference point for cartographic overlays, suggesting that Vistula Fluvius corresponds more closely to the Schwarze Elster (Black Elster) in modern Germany rather than the Vistula (Weichsel) in Poland.

Which geological processes led to a possible regression of the Oceanus Germanicus is not the primary subject of this interpretation, but the author suspects several factors here, which have already been outlined in the publication and which could form a common cause for this. According to the latest considerations, however, the reactivation of the CDF in the course of a late activity phase of the Alpine orogeny (i.e. in more recent times) seems to be a possible main cause. During this event, tectonic forces caused Avalonia to be thrust northward onto the Baltic continental plate, possibly depressing it (potentially a beginning subduction, but temporally limited and regionally restricted to the eastern part of the Avalonian continental plate). As a result, the relative sea level (RSL) along the North German coast would have fallen, leaving areas of the Oceanus Germanicus (on the Baltic continental plate) submerged below sea level.

Both Mount Vesuvius and Mount Etna in Italy, as well as the volcanoes on Iceland, have experienced several large eruptions in the last 3000 years. The famous eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, which destroyed Pompeii, can serve as an example. This suggests a generally high level of geological activity in Europe, which may have led to stresses in the lithosphere and could have potentially triggered or intensified continental drift, even at previously inactive plate boundaries.

A cosmic event with significant tectonic effects is also not entirely ruled out as a possible cause. Such an event could have generated or resolved lithospheric stresses formed tens of thousands of years earlier due to the weight of large glacial ice sheets.

It is also conceivable that a situation similar to the one observed on Jupiter in 1994 occurred, where fragments of the comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, after breaking apart, struck the planet’s surface in succession.[2] A similar event – though likely of a lesser magnitude – might have occurred on Earth within the last 2,000 years. Such an event could potentially be associated with Halley’s Comet, which appeared, for instance, in 530 AD (see “Dallas H. Abbott, Dee Breger, Pierre E. Biscaye, John A. Barron, Robert A. Barron, Robert A. Juhl, Patrick McCafferty, 2014. “What caused terrestrial dust loading and climate downturns between A.D. 533 and 540?“).

In 607 AD, Halley’s Comet was described alongside three other comets [3], which might have been fragments of a larger parent body. According to Babylonian texts, the comet passed close to Jupiter in 164 BC, potentially breaking into several larger pieces. Over subsequent centuries, these fragments could have entered highly divergent orbits due to their size (mass) and the gravitational influences of other celestial bodies.

The impacts of one or more cosmic objects on Earth’s surface could have contributed to the climatic anomaly between 536 and 550 AD [I], a sea-level change, desertification in North Africa, and increased volcanic activity. See also “PAGES 2k Consortium. Continental-scale temperature variability during the past two millennia. Nature Geosci 6, 339–346 (2013)“

These impacts might also relate to the Great Earthquake of Antioch in 526 AD [II] and, in Central Europe, to the collapse of the Thuringian Kingdom around 531 AD.[4] Also conceivable is a connection to the so-called Chiemgau comet, which could have occurred between 2200 BC and 300 BC.

In the year 563 AD, the Tauredunum event also occurred, as recorded in contemporary accounts. This event involved a massive landslide, which triggered a large tsunami in Lake Geneva – possibly the result of significant tectonic stresses on the affected rock formation, potentially linked to an impact event that might have occurred around the same time.

The publication initially assumed post-glacial land uplift to be the main cause of a marine regression, which, in conjunction with the end of a warm period (the Roman climatic optimum), could consequently have led to a falling relative sea level (RSL) on the North German coast. Previously, even less water may have been bound in glacial ice than after the Little Ice Age in the Late Middle Ages – i.e. in the last five hundred years up to almost the present day. The work of Olav Liestøl was used in this consideration, who in the late 1950s evaluated the course of the firn line of western Norwegian glaciers over a period of about 10,000 years (Glaciers of the present day. In: Olaf Holtedahl Geology of Norway. (=Norges Geologiske Undersökelse, Nr. 208). Oslo, 1960.).

Also according to W. Dansgaard et al. (1969), Schönwiese (1995) and Roth (2018), and not least the word etymology of Greenland as “Greenland” [5], already indicate that the average temperature at the time of Ptolemy and during the Middle Ages was higher over longer periods than in the last five hundred years, and that Greenland was initially perceived as green and thus as fertile when it was named. Erik the Red is considered one of the first Vikings to settle Greenland at that time. His life is reported in Nordic sagas, here especially in the Eiríks saga rauða.

It is also conceivable that, during the period between the birth of Christ and the beginning of the Little Ice Age, a significant number of fortifications, castles, and even entire cities were built on shallow waters, former islands, and peninsulas (compare this to the Legend of Vineta, as well as Wikipedia articles on Viking castles, ramparts, and particularly on pile dwellings as found near the Polish towns of Dobiegniew, Chłopowo (Krzęcin), and Lubiatowo (Przelewice)).

On the island groups in northern Germania Magna, Nordic seafaring peoples – ancestors and relatives of the Vikings – may have initially developed (compare also Varangians), or later the Vikings themselves, perhaps due to the expansionist pressure of the Roman Empire, which may have forced the Germanic tribes from the mainland onto the islands in the Oceanus Germanicus – or because they had lost their original settlements due to the previous transgression. The inhabitants of the North may also have temporarily lived on protected marshy islands (Halligen), or it is possible that these structures were later silted up or destroyed by floods, without leaving any traces today.

Due to geological events associated with a shift in the coastline, the Migration Period could also have begun [6], unless warlike conflicts were the primary motive. The Bohemian chronicler Cosmas of Prague, in reference to the later Slavic repopulation of Central Europe by Boemus and his companions, even speaks of a ‘deluge’ by which the land was once deprived of its inhabitants [7].

Considering the present interpretation, the author also considers it possible that historically recorded storm surges in the North– and Baltic Seas could, at least in part, be attributed to tectonic events such as earthquake-induced tsunamis (compare to Mandränke). Here too, a possible cosmic event, as mentioned above, cannot be entirely ruled out as a possible cause. For instance, the uplift of the island of Rügen, likely caused by the thrusting motion of Avalonia due to various events, might have occurred in relatively recent geological times, representing the remaining eroded tip of the Avalonian Plate.

A better understanding of the processes that might have taken place here could potentially lead to improved interpretations of archaeological finds, such as shipwrecks discovered on land [8]. These finds might initially be interpreted as grave goods or so-called boat burials, as they have often been discovered in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. However, in some cases, they could also be remnants of sunken “paddle boats,” which may have been destroyed during battles or catastrophic events in what were originally shallow waters. Such waters might have extended far inland in earlier times if Ptolemy’s records are interpreted correctly here.

Thus, unexpected events like tsunamis or volcanic eruptions could be considered as potential causes for a sunken boat, especially if a future discovery provides evidence of an impact event. Such boats could have been naturally covered by sand and silt through the process of sedimentation later, which might warrant separate consideration when interpreting such finds [III].

*) Supplement of 31.03.2024, Sven Mildner:

possible uplift of the Avalonian continental plate by the mountain building process and the reactivation of the Caledonian Deformation Zone (CDF) (or the formation of a high mountain range in the Oceanus Germanicus)

The onset of Avalonian thrusting may have also led to a stronger crustal thickening in the region of the Netherlands and the North German Wadden Sea. This, in turn, could have resulted in a tilting of the Avalonian continental plate or the surface topography (isostasy). The cause of this may have been a north-south directed force in the context of the Alpine orogeny, which could have led to an uplift of the North German coastal area and the Central European Basin, and perhaps also to a further uplift of the Erzgebirge (Ore mountains) in more recent geological times, or generally to an uplift of the low mountain ranges along the Thuringian-Franconian-Vogtland Slate Mountains, further along the Main river to the Rhenish Slate Mountains, including the Taunus and Hunsrück.

This could also have caused a northwest tilt of the Avalonian continental plate, also because a (limited) obduction onto Baltica could not have occurred equally at all sutures, since Avalonia was overlain by Laurentia in the west. Particularly in the area of Denmark, this likely represents the collision of two continental plates rather than the subduction of oceanic crust, as seen along the western coasts of North and South America. It might be considered a transitional situation.

Please also refer to the work of Lyngsie, S.B. & Thybo, H.. (2007). A new tectonic model for the Laurentia−Avalonia−Baltica sutures in the North Sea: A case study along MONA LISA profile 3. Tectonophysics. 429. 201-227. 10.1016/j.tecto.2006.09.017., which shows that the continental crust of Baltica had already begun to fold in the study area (Caledonian foreland thrust belt), presumably as a prelude to the formation of an accretionary wedge in the Jutland area, with the possible further consequence of a northward displacement of the Sorgenfrei-Tornquist Zone due to the forces acting here.

A comparable event has taken place in the past, for example, to a greater extent in the collision of India with Eurasia (cf. Jiang, Feng & Chen, Xiaobin & Unsworth, Martyn & Cai, Juntao & Han, Bing & Wang, Lifeng & Dong, Zeyi & Tengfa, Cui & Zhan, Yan & Zhao, Guoze & Tang, Ji. (2022). Mechanism for the Uplift of Gongga Shan in the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau Constrained by 3D Magnetotelluric Data. Geophysical Research Letters. 49. 10.1029/2021GL097394.). In essence, this would represent the initial stage of mountain building, which may have been interrupted along the North German coast due to the wedging of three continental plates (Avalonia, Baltica, and Laurentia). Therefore, stronger forces would be required at this point to continue the process, which can already be traced here through the depiction of Germania Magna. Thus, the process of Alpine orogenesis may have shifted in our time from the Alps more towards Scandinavia, depending on the activity of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the force exerted on Europe by the collision with the African continental plate.

It should also be noted that the uplift likely occurred in phases of varying intensity, rather than as a uniform process of mountain building. There must have been periods of heightened activity to produce the necessary landscape changes (geomorphological alterations). In Northern Europe, such processes have rarely been recognized as significant, likely because they are currently in a less conspicuous phase of activity since the advent of modern geosciences.

It is also worth mentioning that the shortening of the continental crust in length obviously also goes hand in hand with its uplift, which leads to graben fractures in the hinterland. (cf. again Jiang, Feng & Chen, Xiaobin & Unsworth, Martyn & Cai, Juntao & Han, Bing & Wang, Lifeng & Dong, Zeyi & Tengfa, Cui & Zhan, Yan & Zhao, Guoze & Tang, Ji. (2022). Mechanism for the Uplift of Gongga Shan in the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau Constrained by 3D Magnetotelluric Data. Geophysical Research Letters. 49. 10.1029/2021GL097394.)

Thus, the Eger Graben may also have been more closely related to this process, or have been caused by earlier (perhaps even periodically occurring) events of the same nature. Likewise, however, it should also be considered whether the Elbe Valley Basin between Meißen and Dresden could ultimately be a result of such processes. In my opinion, the Germania Magna indicates that the area around the Elbe Sandstone Mountains and the Lusatian Mountains could have experienced geomorphological changes in the meantime. According to the description of the Germania Magna, the Erzgebirge was already present, but it is difficult to say whether it may not have experienced another uplift in recent geological times, which is related to the tectonic-induced regression of the Oceanus Germanicus, or a (further) subsidence of the Erzgebirge foreland, as a result of a beginning overthrust of the continental crust at the coast – and, as already indicated, with the associated shortening of the continental crust in the interior of the country – although, according to the previous view, such processes should essentially have taken place at a much earlier point in time. However, even after the relief of the crust by the decrease of the force effect (relaxation), graben structures could probably still form.

It is therefore quite conceivable that there is an even closer connection between the current uplift of Scandinavia and the Alpine orogeny than previously suspected and that the postglacial land uplift could therefore only be partly responsible for this. The comparatively rapid uplift of Scandinavia in modern times could then possibly be attributed to a folding of the continental crust.

The approach of Scandinavia to Central Europe has probably also led to the formation of the North Sea Central Graben, as a bulge of the continental crust (cf. Arfai, J., Franke, D., Lutz, R. et al. Rapid Quaternary subsidence in the northwestern German North Sea. Sci Rep 8, 11524 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29638-6). Former land areas in the North Sea, such as Albionis pars, likely became part of this rift structure and subsequently fell below today’s sea level. This may also have a closer connection to the opening of the Upper Rhine Graben (cf. Mediterranean-Mjösen Zone).

- Dr.-Ing. habil. G. Meier (1998). Historisches zu Erdbeben im Erzgebirge, In: Sächsische Heimatblätter Nr. 20, https://www.dr-gmeier.de/pub/oa0003.pdf

- Video-Dokumentation “Wunder des Weltalls: Folge 09: Der Halleysche Komet”, Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QvgsGHylQeU

- Donald Yeomans – “Comets“, 1991

- Bemmann, J. (2023). Herrschaftswechsel als Zäsur? Thüringen im Frankenreich – eine andere Geschichte. In S. Brather (Ed.), Die Dukate des Merowingerreiches: Archäologie und Geschichte in vergleichender Perspektive (pp. 421-458). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111128818-014 / (Full-Text):

“[…] Conclusion: There were no Frankish military bases on strategically elevated positions, no Frankish military, and no Frankish elites in Central Germany. Integration into the Frankish Empire between 531 and 630 cannot be demonstrated archaeologically. Even if the traditional master narrative accurately described the core of the process and there had been Frankish military stations with garrison troops, these would, judging by the size of the burial grounds, have consisted of only a few men. They would have been hopelessly outnumbered and, in a society without a monopoly on violence where weapon ownership was widespread, would have had no chance of survival. […] (translated)”, and also:

Volkmann, Armin. (2014) “Region im Wandel: Das 5.–6. Jahrhundert n. Chr. im inneren Barbaricum an der unteren Oder und Warthe”- In: Germania Bd. 92 (2014) S. 133-153, including an introduction: “[…] The idea of a gradual transformation is likely only applicable, based on the available archaeological findings, to the Roman Imperial period in the western border regions near the limes, for example in the context of the Romanization of local Germanic groups. However, the findings from the study area (Fig. 1) point instead to drastic upheavals at the end of the Roman Imperial period and during the Migration Period, which in some cases occurred within just a few decades or even years (see Fig. 2 and 3). These processes are not consistent with gradual transformation but rather indicate clear discontinuities resulting from nonlinear changes. In the archaeological evidence from the Migration Period in the Oder region (5th–7th centuries AD), dramatic and deeply impactful processes seem to be reflected. Therefore, the thesis of gradual transformation processes is not applicable to the focused period or the study area. […] (translated)” - Preiser-Kapeller, J. (2020). Der Lange Sommer und die Kleine Eiszeit: Klima, Pandemien und der Wandel der Alten Welt, 500-1500 n. Chr

- Considering an impact theory, approximately between 526–531 AD, this period could at least correspond to ‘a late phase of the Migration Period,’ for example, with the invasion of the Lombards into Italy. Earlier, there had already been conquest campaigns by other Germanic tribes emerging from Germania Magna, such as the Vandals reaching as far as North Africa. However, such an event could also have occurred earlier, perhaps closer to the time around Christ’s birth [IV] or even approximately 10,000 years ago. In this case, the map representation of Germania Magna would also need to be considerably older than previously assumed. A notable change in relative sea level can, for instance, be demonstrated for Scandinavia and was described by Kurt Lambeck, Catherine Smither, and Paul Johnston in ‘Sea-level change, glacial rebound and mantle viscosity for northern Europe,’ Geophysical Journal International, Volume 134, Issue 1, July 1998, Pages 102–144, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-246x.1998.00541.x. This change, however, is very likely, according to current knowledge, primarily related to postglacial land uplift following the end of the Ice Age and apparently occurs over an extended period. Nevertheless, potential dating errors should also be considered here

- F. Biermann: Die frühen Slawen – von Kiew an die Elbe. In: M. Knaut/D. Quast (Hrsg.), Die Völkerwanderung. Europa zwischen Antike und Mittelalter. Arch. Deutschland, Sonderheft 2005 (Stuttgart 2005) 80–84.

- for example, so called: “Usedomer Bootsgräber”, see BIERMANN, Felix. Usedomer Bootsgräber. Germania: Anzeiger der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, 2004, 82. Jg., Nr. 1, S. 159-176.

further references to historical records

- Prokopios von Caesarea, Historien IV 14

[…] during this year a most dread portent took place. The Sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon during this whole year, and it seemed exceedingly like the Sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear.

Author’s note: There may also be a possible connection to the Nordic description of a Fimbulwinter.

- …from the World Chronicle of Michael the Great of Syria concerning the year 525:

The sun became dark and its darkness lasted for 18 months. Each day it shone for about 4 hours, and still this light was only a feeble shadow. Everyone declared that the sun would never recover its full light. The fruits did not ripen and the wine tasted like sour grapes

.In the year A.D. 626, the light of half the sphere of the sun disappeared, and there was darkness from October to June. As a result people said that the sphere of the sun would never be restored to its original state.

During this time, the waters of Shiloh disappeared for 15 years. In this period, fire also fell from the sky and burned the city of Balbek—which had been built by Solomon on Mount Lebanon—as well as its palaces. Yet three stones, which Solomon had placed there as a symbol of the mystery of the Trinity, remained untouched. During the same time, a woman appeared in Cilicia who was a cubit taller than any man and spoke no language. However, she ate human food. She lived for a long time by receiving money from all the shops but then suddenly disappeared. Some said she was a nymph.

In the year 836 of the Syrian era (525 AD), Asklepios, a wicked and corrupt man, was the bishop in Edessa, and he pressured the faithful to accept the unholy Council of Chalcedon. He had 20 miraculous coenobites arrested, cruelly tortured them, and threw them into prison. It happened that, on the second evening, a great flood came down from the mountains. It struck the city walls and receded. The second time, it broke down the walls and flooded the city, killing people and animals by dragging them into the Euphrates. Asklepios saved himself by fleeing into the city’s citadel, as did some others. The people wanted to stone him because they knew he was responsible for this calamity, so he fled to Antioch. There, his fellow sectarian Ephrem, Patriarch of Antioch, said: ‘Behold, brothers, our second Noah has escaped the flood that came because of the sin of not accepting the Council of Chalcedon.’ Justin sent much gold to rebuild Edessa. When they dug, they found an inscription on a stone that read: ‘Three times will a flood strike Edessa.’ This was written in Chaldean script. Thirty thousand bodies were recovered from the flood, while the city’s inhabitants estimated the number of those lost to the waters at 200,000.

Asklepios and Ephrem amused themselves by defiling Antioch with this vile heresy. This brought even more of God’s wrath upon the city. A fifth earthquake shook the entire city, and all buildings, houses, palaces, and churches collapsed. A completely new phenomenon was observed as the wind brought the punishment of Sodom. The river boiled over, and black waters emerged from the depths, carrying crabs, turtles, and the bones of wild animals. The earth spewed fire and water, and deadly fumes rose, bringing death to humans and animals through various afflictions. For several days, fire rained down from the sky like rain. Everyone could hear the screams, but no one dared approach. For one and a half months, the earthquakes and fiery rain continued unabated. The great basilica built by Constantine shook for seven days like a reed in the wind until it split, and fire rose to burn the church. Only 1,250 souls survived these catastrophes. Suddenly, a radiant cross appeared in the sky and disappeared after three days. The people cried out, ‘Lord, have mercy, Lord, have mercy.’

[…] Other regions were also destroyed: Seleucia in Syria by the sea, the city of Daphne, as well as a region twenty miles around Antioch, Anazarbus, the metropolis of Cilicia, and Corinth, the metropolis of Greece. Thus, many people and buildings were lost during the evil years of Justin’s reign.

(translated from a German translation)

- Landscape description of the area along the Elbe and Oder, from Willibald Alexis’ ‘Der falsche Woldemar‘:

First Chapter.

The Old Times.

Around the middle of the fourteenth century, the area between the Elbe and the Oder presented a bleak picture. The Lord, who created heaven and earth, has distributed sunshine unevenly across the lands; but to that region where the German tongue fades and the Slavic begins, His gift of sunlight was sparingly bestowed. It lacked the strength to dry up the marshes left behind by the retreating sea, to penetrate the dense, stubborn forests, or to warm the soil so that it might willingly sustain the generations of people who had been swept there by the tide of nations. To these very generations, the Lord assigned the task of struggling with nature. They were to fashion the land themselves, battling storms and waters, spreading a carpet for the warm sun to linger upon with joy, and creating a country that would be dear to them and pleasing to others.

It was a harsh task, and though centuries have passed since, it remains unfinished even today. They must still labor on, sweating to tame and stabilize the sand that the wind blows away from beneath the plowshare. Yet the work accomplished by the hand and directed by the arm is not enough; for sluggish nature cannot be enlivened by manual labor alone, nor can the sun be forced to shine brighter upon the hard-won land. Bitter toil calls upon the spirit for assistance, to invent new means and to let another light shine where the sun fails to pierce the northern mists.

And how often was this work interrupted—and just when it seemed the harvest was finally within reach! And so terribly and frightfully interrupted that the fearful despaired, and the faint-hearted believed that God’s wrath weighed upon the land, making it futile to resist His hand. But these fates were not the scourges of His wrath; they were trials and fiery ordeals for a generation meant to learn never to lose heart. Just as it struggled against the poverty of the soil and the elements for a better existence, so it was to fight against misfortunes, steeling itself for self-reliance under the blows that always strike the weaker the hardest when mighty powers clash.

(translated from German)

- The Annolied, likely written between 1077 and 1081 by a monk from Siegburg, contains lines that may hint at one or even two well-known geological events of significant magnitude from earlier times. Thus, stanza 27 states:

OY wi di wifini clungin,

Da di marin cisamine sprungin,

Herehorn duzzin,

Becche blütis vluzzin,

Derde diruntini diuniti,

Di helli ingegine gliunte,

Da di heristin in der werilte

Sühtin sich mit suertin.

Dü gelach dir manig breiti scari

Mit blüte birunnin gari,

Da mohte man sin douwen

Durch helme virhouwin

Des richin Pompeiis man

Da Cesar den sige nam.

…and further in stanza 31:

IN des Augusti citin gescahc

Daz Got vane himele nider gesach

Dü ward giborin ein Küning

Demi dienit himilschi dugint,

Iesus Christus Godis Sun

Von der megide Sente Mariun:

Des erschinin san ci Rome

Godis zeichin vrone,

Vzir erdin diz luter olei spranc,

Scone ranniz ubir lant,

Vmbe diu Sunnin ein creiz stunt,

Also roht so viur unti blut,

Wanti dü bigondi nahin,

Dannin uns allin quam diu genade,

Ein niuwe Künincrichi,

Demi müz diu werilt al intwichin.

Draft publication Project website: https://www.germania-magna.de

Mildner, Sven. (2020). The reinterpretation of Claudius Ptolemy’s Germania Magna – with the aid of computer-assisted image distortion of a medieval map by Donnus Nicolaus Germanus – and considerations on the postglacial geodynamics of Europe. 10.23689/fidgeo-5907.

ISBN 979-8573568980

Project website: https://www.germania-magna.de

Note: This edition is an incomplete preliminary release from 2020, as cooperation with university research was unfortunately no longer possible due to political reasons in the course of the Corona crisis. Therefore, the manuscript could not be completed, the content could not be subjected to expert review, and it could not be elaborated into a more comprehensive work until today. The author had to postpone the project due to his civil and societal commitments, but still publishes this preliminary version so that the content can become part of scientific consideration.

The publication quality of the digital edition is unfortunately somewhat limited because the book pages had to be recovered from an already created file copy. As part of his civil engagement to preserve our democracy, combat fascism, and prevent the restriction of our basic rights, the author’s work computer with the original files was confiscated and unlawfully withheld until the day of publication of this draft edition.

Figure content:

A comparative presentation between the medieval Germania Magna map by Donnus Nicolaus Germanus and a colored depiction of current elevation data (DGM).

This image depicts a colored representation of current elevation data (DGM), overlaid with the Germania Magna map by Donnus Nicolaus Germanus.

The location of the Vistula Fluvius [a] on the Germania Magna map, with the Oderbruch and Ziltendorfer Niederung situated in the far east of the map. A transform fault may run here, which could have been caused by a partial thrusting of Avalonia onto the Baltic continental plate (cf. Jiang, Feng & Chen, Xiaobin & Unsworth, Martyn & Cai, Juntao & Han, Bing & Wang, Lifeng & Dong, Zeyi & Tengfa, Cui & Zhan, Yan & Zhao, Guoze & Tang, Ji. (2022). Mechanism for the Uplift of Gongga Shan in the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau Constrained by 3D Magnetotelluric Data. Geophysical Research Letters. 49. 10.1029/2021GL097394.). Oderbruch and Ziltendorfer Niederung could therefore have originated from an earlier valley depression, which was pulled apart or offset along a transform fault.

The previously described situation, applied here in a figurative sense to the considered area of Germania Magna: According to this, the formation of fault zones, such as the Elbe-Lineament, which could have arisen in connection with the presumed uplift of the North German coastal area (with the overthrusting of Avalonia) or the shortening of the continental crust in the interior of the country, which may also be connected with the formation of significant graben structures between the Alps and the Oceanus Germanicus, can possibly also be explained. At the same time, the stronger bulging of the crust between the Netherlands and the North Sea area could have led to a subsidence of the lithosphere (isostasy), with the possible consequence of a change in the tilt of the ground surface and the further uplift of the Ore Mountains as a fault-block mountain range. (North here on the left side of the image, Google Earth Pro, 2024)

A possible course of the Vistula Fluvius [a] might have partially corresponded to the current course of the Schwarze Elster, which, at that time, would not have flowed westward into the (present-day) Elbe (albis fluvii?), but might instead have initially made a bend to the east, following later the course of the Lusatian Neisse from around Guben and continuing into the riverbed of the Oder. Further geological investigations may help clarify this in the future. The location of Stragona could then possibly be assumed near the present-day town of Herzberg (in the district of Elbe-Elster), and Budorigum near Doberlug-Kirchhain. It remains questionable whether the Elbe can actually be identified with its current course, or whether the map rather depicts the course of the Weiße Elster further west (see also the “Excursus on Continental Drift considering Plato’s description of Atlantis” further down on this page). In that case, the location of Nomisterium might be found near Leipzig, or further south toward Gera.

A stronger distortion of the Germania Magna representation is necessary here to adequately match the recorded locations. However, the result of such a map overlay appears to be very plausible. For example, at the confluence of the Schwarze Elster and Spree rivers, which the author initially identifies as the depicted rivers, a medieval fortress (Peitz Fortress) was built in the present-day town of Peitz. It is known that this fortress was surrounded by an old arm of the Spree.

For more information, please visit the following website of the Historical Society of Peitz e.V.: https://festungpeitz.de/

- additional Notes on the term “Vistula Fluvius”:

→ siehe: Additional Notes on the Geography of Germania Magna