a. Note on the term “Vistula Fluvius”:

It is possible that the Greek term Οὐστούλα (Oustoúla) was originally adopted from Latin (i.e., by the Romans), with even older roots potentially found in the Celtic language or possibly that of the Jastorf Culture.

In Latin, the word ustula is the imperative of ustulō and means “to burn something,” “to scorch something,” or also “to consume something with fire” – here to be understood as an order to someone or something to char or smolder something. There is probably also a closer connection to metalworking (especially charcoal burning), which is particularly indicated by the English cognate ustulate – as an adjective meaning “blackened” or “burnt” (Blackened as if burned) and as a verb directly referring to the “burning or roasting of ores” (actually two different processes).

The naming of the river likely referred originally to the smoldering of wood, or directly to the phenomenon of “smouldering fire” (German: Schwelfeuer), as in a charcoal burner used to produce charcoal for bloomery furnaces. As a corresponding possibility of confusion in English, it also refers to the subsequent smelting process, in which the charcoal actually serves (only) as a fuel (ustulate in English as a verb, therefore incorrectly not in the sense of something “smoldering” or in relation to charcoal burning, but – on the contrary, with a strong flame and maximum oxygen supply! here rather to an (more or less arbitrary) example application of the previously obtained charcoal). In contrast, the adjective refers to the color and burning properties of charcoal (which is therefore black, but still combustible, ustulate in English as an adjective).

In this context, the word “pyrolyze” (from pyrolysis) is probably a modern equivalent for essentially the same process, which was probably already described by ustulō, although here one might also speak of “coking” or “carbonization“.

The current name Schwarze Elster (Black Elster) for part of the historical Vistula Fluvius (Oustoúla) could therefore still be a derivation of the original landscape description from the Germanic or Roman period – a description of the river and settlement landscape and probably also of particular features, such as a foreign visitor could have noticed conspicuously on site (e.g., a cartographer or a Roman military officer).

Perhaps something like this, as in this AI-generated example scenario for a Germanic village situated by a minor tributary of the Vistula Fluvius, producing charcoal for metal extraction. Particularly during winter months, when the days in Germania Magna are short, and the nights are cold, the sight of smoke and fire would have been striking in the frost-laden, marshy landscape. Visitors from distant Greece or traveling merchants passing through from the north, bringing amber jewelry to Rome, were likely accustomed to a warmer, Mediterranean climate and urban life in larger cities. Perhaps here in the cold, there was an impressive experience for such a guest – possibly doubling as a translator and cartographer – and even if communication was not so easy, in this inhospitable area, at one of the many fires in the village, they may have tried to talk about this black wood that looks like it had already been burned. It would have been conceivable, just as it steams and smokes from everywhere. The damp fog that pulls over the field from the meadows and almost completely conceals the forest also suggests it: “There must be a lot of fire in this place.” Perhaps the river itself seemed to boil beneath all that rising smoke, obscuring the entire landscape.

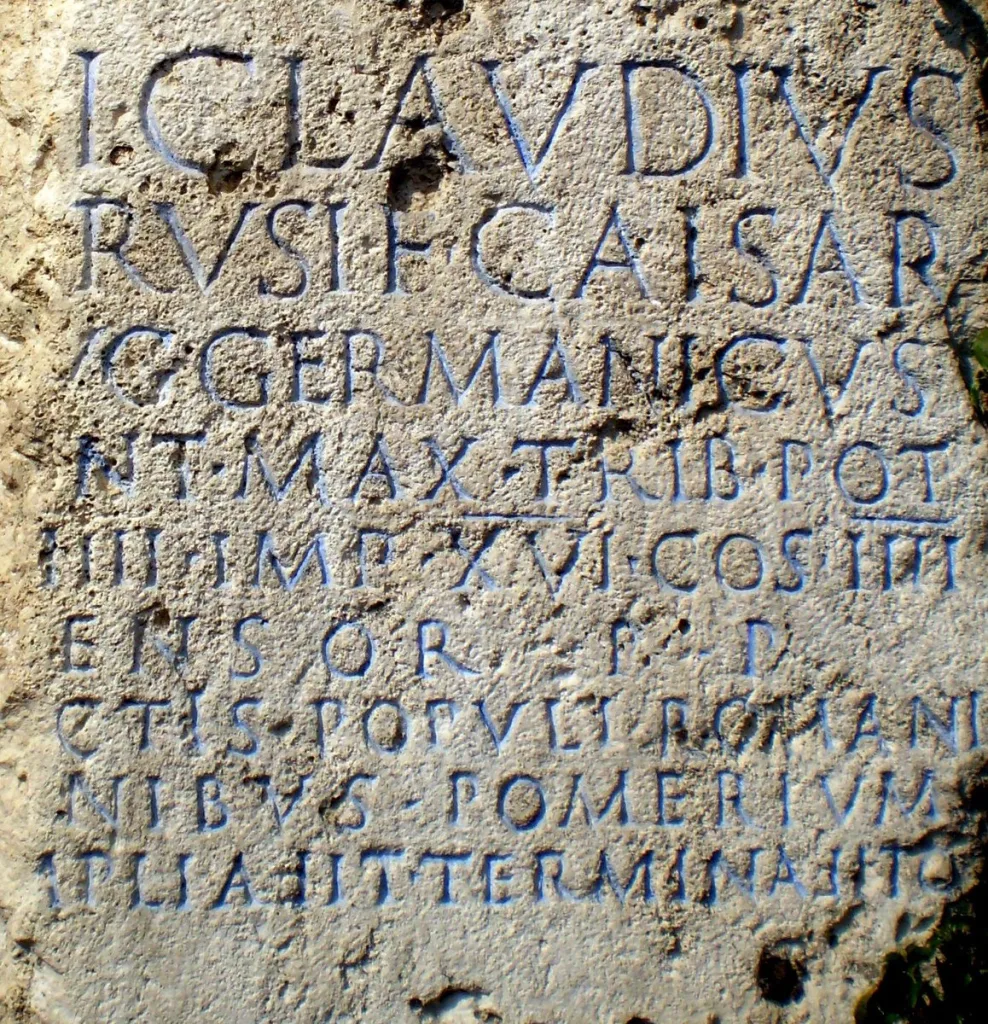

- see The Geography of Claudius Ptolemy in this context

🔊 Vistula Fluvius

Οὐστούλα (Oustoúla)

Etymological Excursion:

In the Flow of Words:

The Vistula in the Dialogue of Cultures

A Not-So-very-Serious Journey Through a possible History of East Germania

(Finno-Ugric Edition)

Tämä gallialainen on oikeastaan työmuuttaja Gotlannista. Tämän joen varrella on verrattuna kylmempään pohjoiseen melko paljon hyttysiä, mutta täällä Havu Hiilivaaraa ansaitsee perustulonsa. Lisäksi puuhiilen kanssa työskentely on omalla tavallaan hyvin meditatiivista, kun tuli polttaa puuta niin hitaasti ja hiillos mustuttaa sitä vähitellen. Puuhiiltä käytetään luonnollisesti ensisijaisesti polttoaineena germaanien monilla kyläjuhlilla, joissa valmistetaan suuri määrä ruokaa koko heimolle ja joissa luonnollisesti myös juodaan paljon simaa. Kuvan vulgaarilatinisti oli kuitenkin kiinnostunut tästä mustasta puusta, joka näyttää jo palaneelta, aivan eri syistä. Rannikolta käsin roomalaiset näyttävät yhä useammin tekevän pieniä isku- ja tiedusteluretkiä syvälle metsiin.

Kun he häiritsevät Havu Hiilivaaraa hänen meditaationsa aikana, hän päättää savustaa koko seudun kunnolla, jotta roomalaiset eivät tiheän sumun keskellä enää näkisi herkynialaista metsää puilta. Loppujen lopuksi tässä metsässä asuvat myös yksisarviset, ja roomalaiset todennäköisesti veisivät ne vain mukanaan sirkukseen Roomaan esitelläkseen niitä yleisölle. Nämä vulgaarilatinistit ovat loppujen lopuksi raakalaisia, joilla ei ole mitään ymmärrystä näiden eläinten mystisestä olemuksesta. Vaikka roomalaiset aluksi kiinnostuvat vain tästä hiilestä, yksisarviset herättäisivät varmasti myös Caesarin ratsuväen kiinnostuksen.

Roomalaiset olivat joka tapauksessa syvästi vaikuttuneita ihmeellisistä olennoista, joita he näkivät vain hyvin ohikiitävästi metsissä. Roomassa puhkesi kuitenkin todellinen mania tämän mustan hiilen vuoksi. Roomalaiset itse kutsuivat sitä “mustaksi maniaksi” (korkealatinaksi “NIGER-MA-NIA”, vulgaarilatinaksi “GERMANIAE”). Roomalainen lääkäri kirjoittaa siitä sen jälkeen, kun Caesar mainitsi toistuvasti näistä yksisarvisista, jotka hän oli nähnyt hiilimetsässä:

Caesar plane maniacus factus est Vult ut unum ex illis unicornibus ex Hercynio carboneo silva capiatur Ei nigra omnia ante oculos videantur nec iam clare cogitare potest Haec est nigramania et certe aliquid ad barbaros pertinet

Est bos cervi figura cuius a media fronte inter aures unum cornu exsistit excelsius magisque directum his quae nobis nota sunt cornibus ab eius summo sicut palmae ramique late divunduntur. Eadem est feminae marisque natura eadem forma magnitudoque cornuum Talia mihi dixit Caesar[2]

Jamuutamiavuosiamyöhemminjopaheidänkeisarinsaottivatitselleennimen

manianmukaanjostahekärsivätjajonkaalkuperäsaattoiollaostulassa[3]

- Hirt. Gal. 6.26.1

- siehe “Vulgärlatein | „Latein. Tot oder lebendig!?“ im Kloster Dalheim“, Stiftung Kloster Dalheim. LWL-Landesmuseum (YouTube Video, 5:03 min)

Conclusion: Thus, we may arrive at a more precise derivation for the Latin ustulō: in the context of charcoal production and use, not only for metal extraction (a connection to English, as outlined above in detail), but also for ritual incense burning (referencing Greek, understood here as “a small form of incense,” cf. frankincense). From Romanian, it could possibly be inferred that the landscape on the Vistula at that time might have been particularly plagued by mosquitoes when the term (per)ustulo entered the language.

Hypothetically, a suitable time frame for such an event could be a period during the (pre-Roman) Iron Age Cold Period, approximately between 900 and 300 BC (see W. Dansgaard et al., One Thousand Centuries of Climatic Record from Camp Century on the Greenland Ice Sheet. Science 166, 377-381 (1969). DOI: 10.1126/science.166.3903.377→), with potentially colder climatic conditions than during the Little Ice Age of the later Middle Ages. The demand for firewood by Nordic civilizations and island inhabitants, who may have settled closer to the Arctic Circle (or generally in colder areas less favored by the Gulf Stream), could have exceeded the local tree resources due to this cooling. As a result, the import of fuel from southern regions might have become necessary. Charcoal, having a significantly lower volumetric weight compared to wood, could have been the preferred material for transport to the north, initially by boat and later, likely on foot. With the appropriate interpretation of Ptolemy’s map or records, it could additionally be assumed that the Sarmatian peoples east of Germania Magna had a close linguistic relationship with the Finno-Ugric peoples, such as the Sami.

Naturally, these are highly speculative assumptions intended to support the etymological derivation of ustulō. However, it could serve as additional evidence for the previously hypothesized convergence and cultural exchange between members of the Latin (or proto-Latin) and Finno-Ugric language families, which may have influenced each other in this region. Possibly as early as the early Iron Age (see Hallstatt culture), coinciding with the beginning of charcoal use for iron production in bloomery furnaces (at the geographical language border between the two language families).

The bloomery (or the use of the bellows to kindle the fire from the glowing charcoal) could be symbolic in this context for the Sampo forged by Ilmarinen, at least on a smaller scale – in a worldly sense. As a reflection of cosmic forces that in their entirety, however, elude our imagination.

Additional Media References:

- Video example for charcoal fire

- Sampo (Film, Sowjetunion, Finnland, 1959)

- Rauta-Aika (The Age of Iron, 1982)

- Map of Celtic Settlement in Europe, between 800 und 300 BC., (Wikipedia-DE: Hallstattzeit)

- The Forging of the Sampo by Väinö Blomstedt [fi], 1897, (Wikipedia-EN: Sampo)

- The Forging of the Sampo, tempera by Joseph Alanen, 1910–1911, (Wikipedia-EN: Ilmarinen)

- Stadt Elsterwerda (Hrsg.): Wo einst Germanen siedelten – Ausgrabungen im Gewerbegebiet-Ost in Elsterwerda (Flyer)

- Archäologische Ausgrabungen, 1992 in Elsterwerda, Stadtfernsehen Elsterwerda/EEF 1992/2016